Sara Ikram Khan1Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â BDS

Sara Ikram Khan1Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â BDS

Shama Asghar2Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â BDS, FCPS

Syed Muhammad Faizan3Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â BDS

INTRODUCTION:

The aim of this study was to collect information from dentists regarding treatment of endodontic emergencies and investigate their antibiotic prescribing habits.

METHODOLOGY: A cross sectional study was conducted in which questionnaires were distributed to 300 dentists of dental hospitals and private clinics of Karachi, Pakistan. The survey dealt with questions focusing on treatment approaches for different endodontic emergency situations and antibiotic prescribing habits of the dentists.

RESULTS: A total of 182 participants were included with a response rate of 65%. In cases of a vital teeth with irreversible pulpitis, (59.9%) of dentists opted for two visit root canal treatment. Dentists with working experience 5 years performed root canal treatment in more than two visits which is in a higher ratio than the other groups (P<0.05). (75.3%) of dentists prescribed medications if RCT required multiple visits. (33.5%) managed emergency case of pulpitis by pulpectomy in combination with analgesics and antibiotics. In management of acute apical periodontitis, (28%) opted for pulpectomy with intra-canal medication. In case of acute apical abscess, (67.6%) of the dentists preferred drainage of the abscess by opening pulp chamber in combination with antibiotics. Most frequently prescribed antibiotics were Amoxicillin-Clavulanate (78.8%).

CONCLUSIONS: Dentists were over prescribing antibiotics in may conditions. Educational programs should be conducted on regular basis to increase the knowledge of the dentists.

KEY WORDS: Endodontic emergencies, Root Canal Treatment, Antibiotic prescription, Dentists.

HOW TO CITE: Â Khan SI, Asghar S, Faizan SM. Current trends to deal endodontic emergencies and use of antibiotics by dentists of karachi. J Pak Dent Assoc 2018;27(1):18-21.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25301/JPDA.271.18

Received: 23 November, 2017,  Accepted: 08 December, 2017

INTRODUCTION

Dental emergencies usually include severe pain, swelling and abscess formation which are dealt on daily basis by either endodontic treatment or extraction of the tooth.1 Dental emergencies are usually a result of untreated irreversible pulpitis characterized by spontaneous episodes of sharp shooting and lingering pain which is due to irreparable pulpal damage2 and if not treated can lead to pulp necrosis and abscess formation. Fractured and cracked tooth that involves pulp can also lead to similar episodes of pain3 and require RCT or extraction. These situations are further dealt with systemic antibiotics and analgesics for relief of symptoms as an adjunctive treatment if indicated.1

However, literature does not present much evidence to support use of antibiotic for pain relief4,5 and unnecessary prescription of systemic antibiotics leads to systemic side effects, allergic reactions and antibiotic resistance.6,7 Dentists need to be educated about the antibiotic prescription guidelines and should only prescribe antibiotics if it is clearly indicated.1,2,4,6,7 The aim of this study is to collect information about the knowledge and practice of the dental practitioners of Karachi regarding endodontic emergencies and also investigate their antibiotic prescribing habits.

METHODOLOGY

It was a cross-sectional, multi-center study. A two-page content validated questionnaire was prepared in English language as our study tool. The ethical approval was obtained by the ethical review committee of Bahria University Medical and Dental College. The questionnaire was pilot testing by 7 dentists each from 3 different dental hospitals and 4 private practitioners before data collection. The questionnaire was then distributed to 300 dentists of private dental clinics as well as dental hospitals associated with institutes in Karachi, Pakistan. Consent was obtained from the respondents and no names were asked to ensure anonymity.

The questionnaire was divided into two parts; the first comprised of questions regarding years of professional activity, number of appointments dentists took for treating vital and non-vital teeth, number of appointments dentists took for single rooted and multi-rooted teeth and whether they prescribed analgesics and antibiotics in between the appointments. The second part focused on different treatment approaches in various endodontic emergencies like irreversible pulpitis, acute apical periodontitis, acute apical abscess and lastly the most commonly prescribed antibiotics were asked. Data analysis was done on IBM SPSS Statistics version 20. Frequency tables were prepared and statistical analysis using chi square test was done and P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

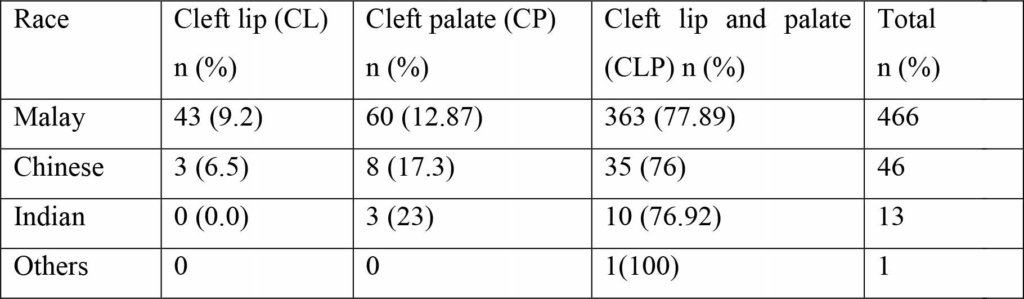

Of the 300 questionnaires that were distributed, 195 dentists responded and returned the questionnaires among which 13 were excluded due to incomplete information. Over all response rate was 65% (n=182). In cases of a vital teeth with irreversible pulpitis, (59.9%) of dentists opted for two visits for root canal treatment, while (33.5%) opted for more than two visits. Dentists who had a working experience of less than 5 years performed root canal treatment in more than two visits which is in a higher ratio than the other groups (P<0.05) (Table 1). (52.7%) practitioners preferred multiple visits for treatment of a non

vital tooth. (51%) practitioners opted for a single-visit root canal treatment for incisors and canines, (63.2%) opted for double visits in case of premolars and for (76.4%) preferred three or more visits for molars. (75.3%) of dentists prescribed medications if RCT required multiple visits. (47.8%) of respondents managed emergency case of irreversible pulpitis by pulpectomy in combination with analgesics whereas (33.5%) dentists prescribed antibiotics in addition to pulpectomy and analgesics. Only (2.7%) of respondents opted for analgesics and antibiotics for this case. Rate of antibiotic prescription by dentists with working experience of 6-15 years was significantly lower than the young practitioners (P<0.05) (Table 2).

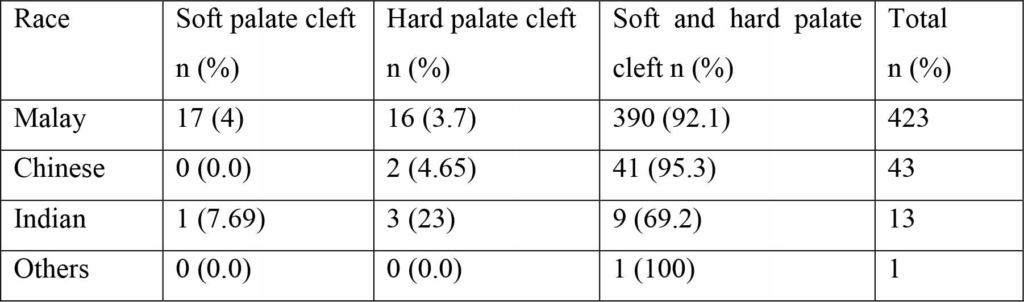

Cases of acute apical periodontitis (51.1%) of the respondents opted for pulpectomy in combination with analgesics and antibiotics while (28%) used pulpectomy with the use of intra-canal medication. (17.6%) of the dentists managed the case with analgesics and antibiotics.

In case of acute apical abscess, (67.6%) of the dentists opted for drainage of the abscess by opening pulp chamber in combination with antibiotics. (24.2%) dealt the case just by opening the pulp chamber and draining the abscess. Most frequently prescribed antibiotics were AmoxicillinClavulanate (78.8%), Metronidazole (47.3%) and amoxicillin (45.1%) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study included dentists from dental hospitals as well as private clinics of Karachi, Pakistan to investigate the current trends of endodontic emergency approaches and their antibiotic prescribing habits. Our results showed that 33.5% of dentists prescribed antibiotics for treatment of irreversible pulpitis which is significantly higher than 1.7% in US8, 4.3% in Belgium9, 6.1% in Turkey10 but comparable to 31.5% in Spain11 and 37.6% in India.12 Studies have shown that use of antibiotics is not indicated in case of irreversible pulpitis.13 “Antibiotics do not appear to significantly reduce toothache caused by irreversible pulpitis”5 and “Immediate pulpectomy is now widely accepted as the ‘standard of care’ for irreversible pulpitis”.14 17.6% of respondents in our study treated acute apical periodontitis with antibiotics only, which is less than 54.3% in Spain11, 31.2% in Saudi Arabia15 and 71.6% in India.12 In acute peri-apical periodontitis the pulp shows vitality and hence there is no need to prescribe antibiotics. In acute per-radicular abscess, 67.6% dentists preferred draining the pus by opening the pulp chamber along with the antibiotic coverage. This value is more than 51.76% in Lebanon16 and less than 83.3% in Saudi arabia17, 71.5% in Brazil18, the proposed treatment for acute apical abscess focuses on removing the cause of infection and reducing the bacterial load. This usually involves drainage of the pus and root canal treatment. Antibiotic coverage is usually not necessary in localized and uncomplicated apical abscesses and host’s immune system usually resolves the infection.

However, if there is a sign of “systemic involvement including fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, cellulitis, progressive swelling and/or trismus; and abscesses in medically compromised patients”19 then antibiotics are indicated in addition to local treatment. Most frequently prescribed antibiotic in our study was Amoxicillin-Clavulanate (78.8%) which is in contrast to a study done in US and Brazil where amoxicillin was the first choice of drug (60.71% and 81.5% respectively).20,18 Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid is found to be associated with more adverse reactions in comparison to amoxicillin and therefore this should be used only in cases where there is systemic involvement or patient is immunocompromised.20

CONCLUSION

There is a lack of knowledge among practitioners about the indications of antibiotics. Dentists were over prescribing antibiotics in cases where local treatment would have been sufficient. Educational programs should be conducted on regular basis to increase the knowledge of the dentists and recommended antibiotic prescription guidelines should be re-enforced.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- Dailey Y, Martin M. Therapeutics: are antibiotics being used appropriately for emergency dental treatment? Br Dent J. 2001;191(7):391-393. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801190

- Sutherland S. Antibiotics do not reduce toothache caused by irreversible pulpitis. Evidence-Based Dentistry. 2005;6(3):67-67. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400340

- Alkhalifah S, Alkandari H, Sharma P, Moule A. Treatment of Cracked Teeth. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(9):1579-

1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2017.03.029 - MartÃn-Jiménez M1, MartÃn-Biedma B2, López-López J3, Alonso-Ezpeleta O4, Velasco-Ortega E5, Jiménez-Sánchez MC1, Segura-Egea JJ1. Dental students’ knowledge regarding the indications for antibiotics in the management of endodontic infections. Int Endod J. 2018 Jan;51(1):118-127. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12778

- Agnihotry A, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ, Farman AG, Al-Langawi JH. Antibiotic use for irreversible pulpitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Feb 17;2:CD004969. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004969.pub4

- Segura-Egea J, MartÃn-González J, Jiménez-Sánchez M, Crespo-Gallardo I, Saúco-Márquez J, Velasco-Ortega E. Worldwide pattern of antibiotic prescription in endodontic infections. International Dental Journal. 2017;67(4):197- 205. https://doi.org/10.1111/idj.12287

- Longman L, Preston A, Martin M, Wilson N. Endodontics in the adult patient: the role of antibiotics. Journal of Dentistry. 2000;28(8):539-548. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-5712(00)00048-8

- Yingling NM, Byrne BE, Hartwell GR. Antibiotic use by members of the American association of endodontists in the year 2000: report of a national survey. Journal of Endodontics 2002;28(5):396-404. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004770-200205000-00012

- Mainjot A, D’Hoore W, Vanheusden A, Van Nieuwenhuysen J. Antibiotic prescribing in dental practice in Belgium. International Endodontic Journal. 2009;42(12):1112-1117.

- Khan SI/ Asghar S/ Faizan SM Current trends to deal endodontic emergencies 226 JPDA Vol. 27 No. 01 Jan-Mar 2018 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01642.x

- Segura-Egea J, Velasco-Ortega E, Torres-Lagares D, Velasco-Ponferrada M, Monsalve-Guil L, Llamas-Carreras J. Pattern of antibiotic prescription in the management of endodontic infections amongst Spanish oral surgeons. International Endodontic Journal. 2010;43(4):342-350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01691.x

- Konde S, Jairam L, Peethambar P, Noojady S, Kumar N. Antibiotic overusage and resistance: A cross-sectional survey among pediatric dentists. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. 2016;34(2):145. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-4388.180444

- Nagle D, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. Effect of systemic penicillin on pain in untreated irreversible pulpitis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2000;90(5):636-640. https://doi.org/10.1067/moe.2000.109777

- Alattas H, Alyami S. Prescription of antibiotics for pulpal and periapical pathology among dentists in southern Saudi Arabia. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2017;9:82-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2017.01.012

- Asmar G, Cochelard D, Mokhbat J, Lemdani M, Haddadi A, Ayoub F. Prophylactic and Therapeutic Antibiotic Patterns of Lebanese Dentists for the Management of Dentoalveolar Abscesses. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice. 2016;17:425-433. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1867

- AlRahabi M, Abuong Z. Antibiotic abuse during endodontic treatment in private dental centers. Saudi Medical Journal. 2017;38(8):852-856. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.8.19373

- Siqueira J, Rocas I. Microbiology and Treatment of Acute Apical Abscesses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2013;26(2):255-273. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00082-12

- Germack M, Sedgley C, Sabbah W, Whitten B. Antibiotic Use in 2016 by Members of the American Association of Endodontists: Report of a National Survey. Journal of Endodontics. 2017;43(10):1615-1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2017.05.009